Part 3 - Writing and Breaking Properties

Introduction and Goals

In this section we'll finally get to exploring the reason why invariant testing is valuable: breaking properties, but first we need to understand how to define and implement them.

For the recorded stream of this part of the bootcamp see here.

Additional points on Chimera architecture

In parts 1 and 2 we primarily looked at targets defined in the MorphoTargets contract, but when you scaffold with Chimera you also get the AdminTargets, DoomsdayTargets and ManagersTargets contracts generated automatically.

We'll look at each of these more in depth below but before doing so here's a brief overview of each:

AdminTargets- target functions that should only be called by a system admin (uses theasAdminmodifier to call as our admin actor)DoomsdayTargets- special tests with multiple state changing operations in which we add inlined assertions to test specific scenariosManagersTargets- target functions that allow us to interact with any manager used in our system (ActorManagerandAssetManagerare added by default)

The three types of properties

When discussing properties it's easy to get caught-up in the subtleties of the different types, but for this overview we'll just stick with three general ideas for properties that will serve you well.

If you want to learn more about the subtleties of different property types, see this section on implementing properties.

1. Global Properties

Global properties, as the name implies, make assertions on the global state of the system, which can be defined by reading values from state variables or by added tracking variables that define values not stored by state variables.

An example of a global property that can be defined in many system types is a solvency property. For a solvency property we effectively query the sum of balances of the token, then query the balance in the system and make an assertion:

/// @dev simple solvency property that checks that a ERC4626 vault always has sufficient assets to exchange for shares

function property_solvency() public {

address[] memory actors = _getActors();

// sums user shares of the vault token

uint256 sumUserShares;

for (uint256 i; i < actors.length; i++) {

sumUserShares += vault.balanceOf(actors[i]);

}

// converts sum of user shares to vault's underlying assets

uint256 sharesAsAssets = vault.convertToAssets(sumUserShares);

// fetches underlying asset balance of vault

uint256 vaultUnderlyingBalance = IERC20(vault.asset()).balanceOf(address(vault));

// asserts that the vault must always have a sufficient amount of assets to repay the shares converted to assets

gte(vaultUnderlyingBalance, sharesAsAssets, "vault is insolvent");

}

In the above example, any time the system's balance is less than the sum of shares converted to the underlying asset, the system is insolvent because it would be unable to fulfill all repayments.

Interesting states that can be checked with global properties usually either take the form of one-to-one variable checks like checking a user balance versus balance tracked in the system or aggregated checks like the sum of all user balances versus sum of all internal balances.

2. State Changing Properties

State changing properties allow us to verify how the state of a system evolves over time with calls to state changing functions.

For example, we could verify that for a deposit into a vault, a user's balance of the share token is increased by the correct amount:

/// @dev inline property to check that user isn't minted more shares than expected

function vault_deposit(uint256 assets, address receiver) public {

// fetch the amount of expected shares to be received for depositing a given amount of assets

uint256 expectedShares = vault.previewDeposit(assets);

// fetch user shares before deposit

uint256 sharesBefore = vault.balanceOf(receiver);

// make the deposit

vault.deposit(assets, receiver);

// fetch user shares after deposit

uint256 sharesAfter = vault.balanceOf(receiver);

// assert that user doesn't gain more shares than expected

lte(sharesAfter, sharesBefore + expectedShares, "user receives more than expected shares");

}

The check in the above goes a step beyond a simple equality check and confirms that the user doesn't gain more shares than expected. This is helpful for finding issues where the vault may round in favor of the user instead of the protocol, potentially leading to insolvency.

Although these types of checks may seem basic, you'd be surprised how many times they've led to uncovering edge cases in private audits for the Recon team.

Dealing with complex tests

Global and state changing properties allow making an assertion after an individual state change is made, but sometimes you'll want to check how multiple specific state changes affect the system.

For these checks you can use the stateless modifier which reverts all state changes after the function call:

modifier stateless() {

_;

revert("stateless");

}

This allows you to perform the specific check without maintaining state changes in the next target function call.

Adding the stateless modifier to functions defined in DoomsdayTargets therefore lets us test specific cases which make multiple state changes or modify the input to the target function in some way. For example, we can check if withdrawing a user's entire maxWithdraw amount from a vault sets the user's maxWithdraw to 0 after:

function doomsday_maxWithdraw() public stateless {

uint256 maxWithdrawBefore = vault.maxWithdraw(_getActor());

vault.withdraw(amountToWithdraw, _getActor(), _getActor());

uint256 maxWithdrawAfter = vault.maxWithdraw(_getActor);

eq(maxWithdrawAfter, 0, "maxWithdraw after withdrawing all is nonzero");

}

If the assertion above fails, we'll get a reproducer unit test in which the doomsday_maxWithdraw function is the last one called. If the assertion doesn't fail, the fuzzer will revert the state changes meaning it won't be included in the shrunken reproducer for any other broken properties. As a result, the function that's used for exploring state changes related to withdrawals will be the primary withdrawal handler function: vault_withdraw.

Using this technique ensures that the actual state exploration done by the fuzzer is handled only by the target functions which call one state changing function at a time and have descriptive names. This approach keeps what we call the "story" clean, where the story is the call sequence that's used to break a property in a reproducer unit test. Having each individual handler responsible for one state changing call makes it easier to understand how the state evolves when looking at the test.

Practical exercise: RewardsManager

For our example we'll be looking at the RewardsManager contract, in this repo.

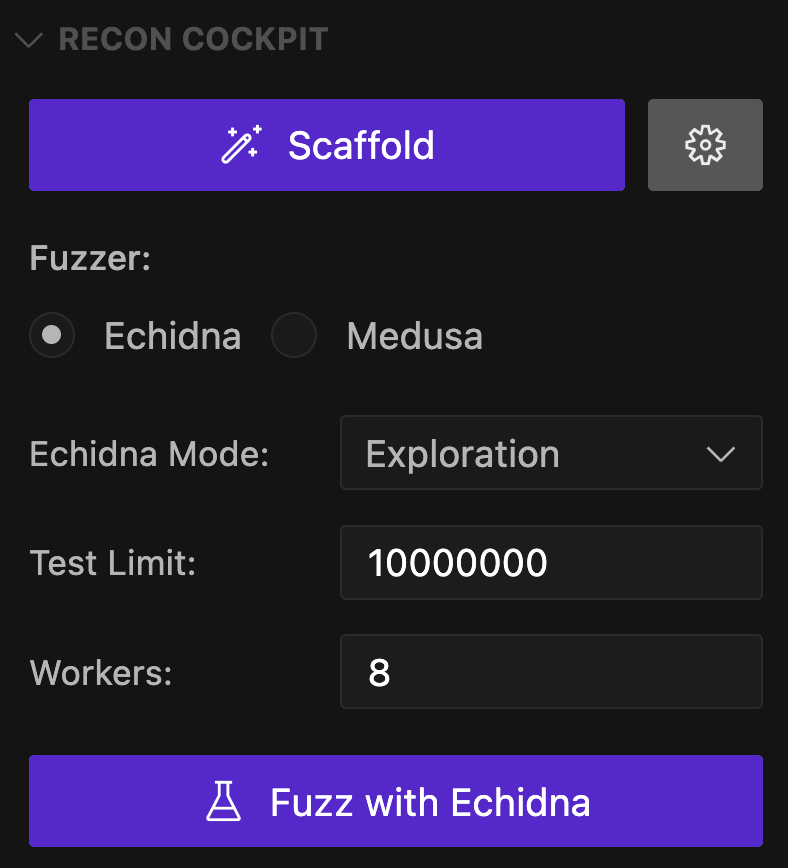

First we'll use the Recon extension to add a Chimera scaffolding to the project like we did in part 1, then focus on how we can get full coverage and finally implement the properties.

This is typically how we structure our engagements at Recon, as we outlined in this section of the intro as these steps need to preceed one another to be maximally effective and reduce the amount of time spent debugging issues.

Scaffolding

We can use the same process for scaffolding as we did in part 1. After scaffolding the RewardsManager, we should have the following target functions:

abstract contract RewardsManagerTargets is

BaseTargetFunctions,

Properties

{

function rewardsManager_accrueUser(uint256 epochId, address vault, address user) public asActor {

rewardsManager.accrueUser(epochId, vault, user);

}

function rewardsManager_accrueVault(uint256 epochId, address vault) public asActor {

rewardsManager.accrueVault(epochId, vault);

}

function rewardsManager_addBulkRewards(uint256 epochStart, uint256 epochEnd, address vault, address token, uint256[] memory amounts) public asActor {

rewardsManager.addBulkRewards(epochStart, epochEnd, vault, token, amounts);

}

function rewardsManager_addBulkRewardsLinearly(uint256 epochStart, uint256 epochEnd, address vault, address token, uint256 total) public asActor {

rewardsManager.addBulkRewardsLinearly(epochStart, epochEnd, vault, token, total);

}

function rewardsManager_addReward(uint256 epochId, address vault, address token, uint256 amount) public asActor {

rewardsManager.addReward(epochId, vault, token, amount);

}

function rewardsManager_claimBulkTokensOverMultipleEpochs(

uint256 epochStart,

uint256 epochEnd,

address vault,

address[] memory tokens,

address user

) public asActor {

rewardsManager.claimBulkTokensOverMultipleEpochs(epochStart, epochEnd, vault, tokens, user);

}

function rewardsManager_claimReward(uint256 epochId, address vault, address token, address user) public asActor {

rewardsManager.claimReward(epochId, vault, token, user);

}

function rewardsManager_claimRewardEmitting(uint256 epochId, address vault, address token, address user) public asActor {

rewardsManager.claimRewardEmitting(epochId, vault, token, user);

}

function rewardsManager_claimRewardReferenceEmitting(uint256 epochId, address vault, address token, address user) public asActor {

rewardsManager.claimRewardReferenceEmitting(epochId, vault, token, user);

}

function rewardsManager_claimRewards(

uint256[] memory epochsToClaim,

address[] memory vaults,

address[] memory tokens,

address[] memory users

) public asActor {

rewardsManager.claimRewards(epochsToClaim, vaults, tokens, users);

}

function rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(address from, address to, uint256 amount) public asActor {

rewardsManager.notifyTransfer(from, to, amount);

}

function rewardsManager_reap(RewardsManager.OptimizedClaimParams memory params) public asActor {

rewardsManager.reap(params);

}

function rewardsManager_tear(RewardsManager.OptimizedClaimParams memory params) public asActor {

rewardsManager.tear(params);

}

}

Since the RewardsManager has no constructor arguments, we can see that the project immediately compiles without needing to modify our setup function:

forge build

[⠊] Compiling...

[⠑] Compiling 56 files with Solc 0.8.24

[⠘] Solc 0.8.24 finished in 702.49ms

Compiler run successful!

letting us move onto the next step of expanding our setup to improve our line and logical coverage.

Setting up actors and assets

The first step for improving our test setup will be adding three additional actors and token deployments of varying decimal values to the setup function:

function setup() internal virtual override {

rewardsManager = new RewardsManager();

// Add 3 additional actors (default actor is address(this))

_addActor(address(0x411c3));

_addActor(address(0xb0b));

_addActor(address(0xc0ff3));

// Deploy MockERC20 assets

_newAsset(18);

_newAsset(8);

_newAsset(6);

// Mints to all actors and approves allowances to the counter

address[] memory approvalArray = new address[](1);

approvalArray[0] = address(rewardsManager);

_finalizeAssetDeployment(_getActors(), approvalArray, type(uint88).max);

}

Note that in the

ActorManager, the default actor isaddress(this)which also serves as the "admin" actor which we use to call privileged functions via theasAdminmodifier.

The RewardsManager doesn't implement access control mechanisms, but we can simulate privileged functions only being called by the admin actor using the CodeLense provided by the Recon extension to replace the asActor modifier with the asAdmin modifier on our functions of interest:

and subsequently relocating these functions to the AdminTargets contract. In a real-world setup this allows testing admin functions that would be called in regular operations by ensuring these target functions are always called with the correct actor so they don't needlessly revert.

We'll apply the above mentioned changes to the rewardsManager_addBulkRewards, rewardsManager_addBulkRewardsLinearly, rewardsManager_addReward and rewardsManager_notifyTransfer functions:

abstract contract AdminTargets is

BaseTargetFunctions,

Properties

{

function rewardsManager_addBulkRewards(uint256 epochStart, uint256 epochEnd, address vault, address token, uint256[] memory amounts) public asAdmin {

rewardsManager.addBulkRewards(epochStart, epochEnd, vault, token, amounts);

}

function rewardsManager_addBulkRewardsLinearly(uint256 epochStart, uint256 epochEnd, address vault, address token, uint256 total) public asAdmin {

rewardsManager.addBulkRewardsLinearly(epochStart, epochEnd, vault, token, total);

}

function rewardsManager_addReward(uint256 epochId, address vault, address token, uint256 amount) public asAdmin {

rewardsManager.addReward(epochId, vault, token, amount);

}

function rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(address from, address to, uint256 amount) public asAdmin {

rewardsManager.notifyTransfer(from, to, amount);

}

}

This leaves our RewardsManagerTargets cleaner and makes it easier to distinguish user actions from admin actions.

Creating clamped handlers

Looking at our target functions we can see there are 3 primary values that we'll need to clamp if we don't want the fuzzer to spend an inordinate amount of time exploring states that are irrelevant: address vault, address token and address user:

abstract contract RewardsManagerTargets is

BaseTargetFunctions,

Properties

{

...

function rewardsManager_accrueUser(uint256 epochId, address vault, address user) public asActor {

rewardsManager.accrueUser(epochId, vault, user);

}

...

function rewardsManager_claimRewardEmitting(uint256 epochId, address vault, address token, address user) public asActor {

rewardsManager.claimRewardEmitting(epochId, vault, token, user);

}

...

}

Thankfully our setup handles tracking for two of the values we need, so we can clamp token with the value returned by _getAsset() and the user with the value returned by _getActor(). For simplicity we'll clamp the vault using address(this), this saves us from having to implement a mock vault which we'd have to add to our actors to call the handlers with.

We'll start off by only clamping the claimReward function because it should allow us to reach decent coverage after our first run of the fuzzer:

abstract contract RewardsManagerTargets is

BaseTargetFunctions,

Properties

{

function rewardsManager_claimReward_clamped(uint256 epochId) public asActor {

rewardsManager_claimReward(epochId, address(this), _getAsset(), _getActor());

}

}

We can then run Echidna in exploration mode (which only tries to increase coverage without testing properties) for 10-20 minutes to see how many of the lines of interest get covered with this minimal clamping applied:

Coverage analysis

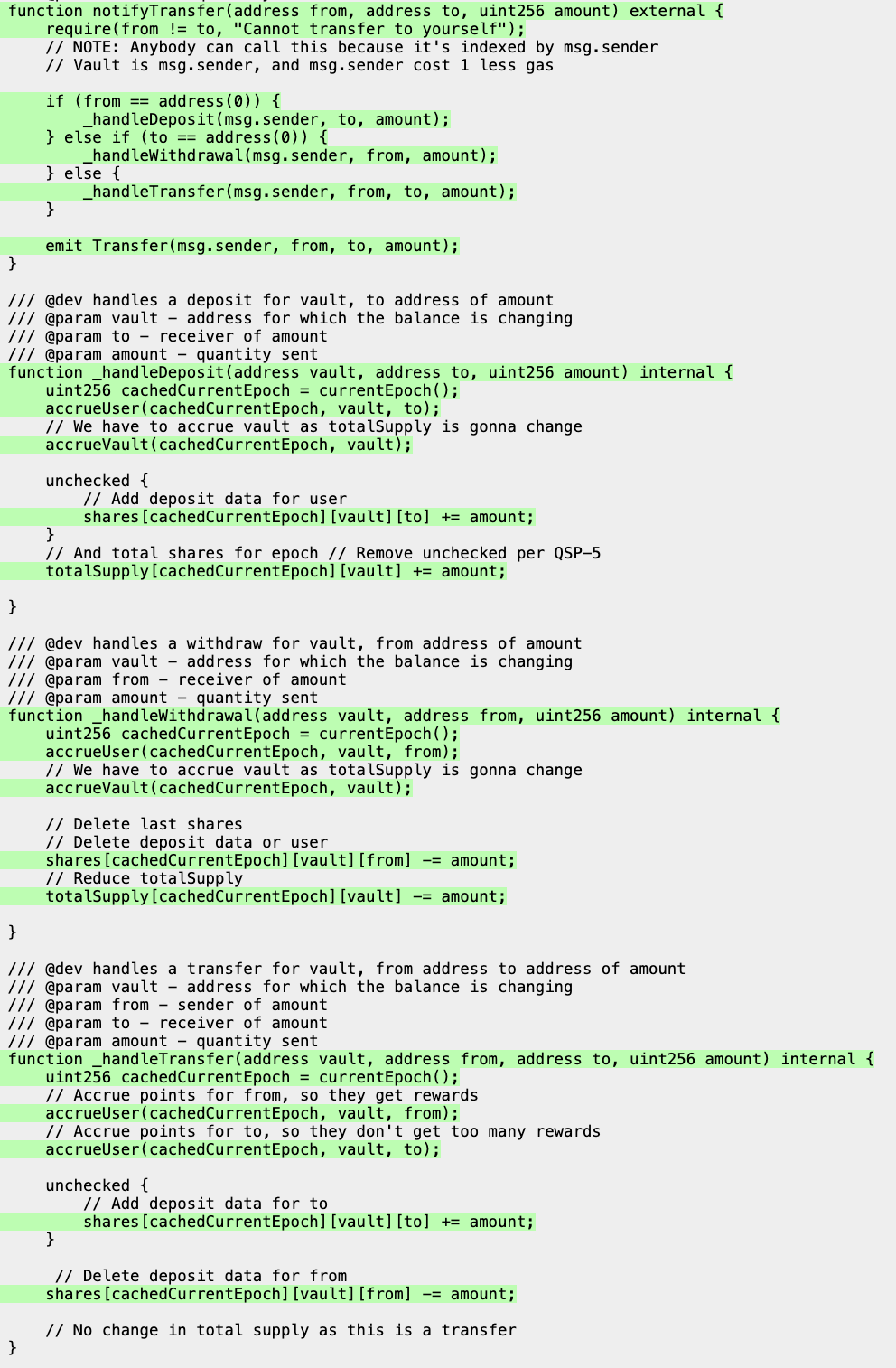

After stopping the fuzzer, we can see from the coverage report that all the major functions of interest: notifyTransfer, _handleDeposit, _handleWithdrawal, _handleTransfer, and accrueVault are fully covered:

We can also see, however, that the claimReward function is only being partially covered:

specifically, the epoch for which a user is claiming rewards never has any points accumulated for it, so it never has anything to claim.

We can use this additional information to improve our rewardsManager_claimReward_clamped function further:

function rewardsManager_claimReward_clamped(uint256 epochId) public asActor {

uint256 maxEpoch = rewardsManager.currentEpoch();

epochId = epochId % (maxEpoch + 1);

rewardsManager_claimReward(epochId, address(this), _getAsset(), _getActor());

}

which ensures that we only claim rewards for an epochId that has already passed, which makes it more likely that there will be points accumulated for it.

We can then start a new run of the fuzzer and confirm that this has improved coverage as expected:

Now with a setup that works and coverage over the functions of interest we can move on to the property writing phase.

About the RewardsManager contract

Before implementing the properties themselves we need to get a high-level understanding of how the system works. This is essential for effective invariant testing when you're unfamiliar with the codebase because it helps you define meaningful properties.

Typically if you designed/implemented the system yourself you'll already have a pretty good idea of what the properties you want to define are so you can skip this step and start defining properties right away.

The RewardsManager, as the name implies, is meant to handle the accumulation and distribution of reward tokens for depositors into a system. Since token rewards are often used as an incentive for providing liquidity to protocols, typically via vaults, this contract is meant to integrate with vaults via a notification system which is triggered by user deposits/withdrawals/transfers. This subsequently updates reward tracking for a user so any holder of the vault token can receive rewards proportional to the amount of time for which they're deposited.

The key function in the notification system that handles this is notifyTransfer:

function notifyTransfer(address from, address to, uint256 amount) external {

require(from != to, "Cannot transfer to yourself");

if (from == address(0)) {

_handleDeposit(msg.sender, to, amount);

} else if (to == address(0)) {

_handleWithdrawal(msg.sender, from, amount);

} else {

_handleTransfer(msg.sender, from, to, amount);

}

emit Transfer(msg.sender, from, to, amount);

}

which decrements or increments the reward tracking for a given user based on the action taken.

Looking at the _handleDeposit function more closely:

function _handleDeposit(address vault, address to, uint256 amount) internal {

uint256 cachedCurrentEpoch = currentEpoch();

accrueUser(cachedCurrentEpoch, vault, to);

// We have to accrue vault as totalSupply is gonna change

accrueVault(cachedCurrentEpoch, vault);

unchecked {

// Add deposit data for user

shares[cachedCurrentEpoch][vault][to] += amount;

}

// Add total shares for epoch // Remove unchecked per QSP-5

totalSupply[cachedCurrentEpoch][vault] += amount;

}

we can see that it accrues rewards to the user and the vault based on the time since the last accrual. It then increases the shares accounted to the user for the current epoch which determine a user's fraction of the total rewards as a fraction of the total shares for the epoch.

Initial property outline

Now that we have an understanding of how the system works, we can define our first properties.

From the above function we can define a solvency property as: "the totalSupply of tracked shares is the sum of user share balances":

totalSupply == SUM(shares[vault][users])

which ensures that we never have more shares accounted to users than the totalSupply we're tracking.

In addition to the solvency property, we can also define a property that states that: "the sum of accumulated rewards are less than or equal to the reward token balance of the RewardsManager":

SUM(rewardsInfo[epochId][vaultAddress][tokenAddress]) <= rewardToken.balanceOf(address(rewardsManager))

Implementing the first properties

Often it's good to write out properties as pseudo-code before implementing in Solidity because it allows us to understand which values we can read from state and which we'll need to add additional tracking for.

In our case we can use our property definitions:

- the

totalSupplyof shares tracked is the sum of user share balances - the sum of rewards are less than or equal to the reward token balance of the

RewardsManager

To outline the following pseudocode:

## Property 1

For each epoch, sum all user share balances (`sharesAtEpoch`) by looping through all actors (returned by `_getActors()`)

Assert that `totalSupply` for the given epoch is the same as the sum of shares `totalSupply == sharesAtEpoch`

## Property 2

For each epoch, sum all rewards for `address(this)` (our placeholder for the vault)

Using the sum of the above, assert that `total <= token.balanceOf(rewardsManager)`

Implementing the total supply solvency property

We can then use the pseudocode to guide the implementation of the first property in the Properties contract:

function property_totalSupplySolvency() public {

// fetch the current epoch up to which rewards have been accumulated

uint256 currentEpoch = rewardsManager.currentEpoch();

uint256 epoch;

while(epoch < currentEpoch) {

uint256 sharesAtEpoch;

// sum over all users

for (uint256 i = 0; i < _getActors().length; i++) {

uint256 shares = rewardsManager.shares(epoch, address(this), _getActors()[i]);

sharesAtEpoch += shares;

}

// check that sum of user shares for an epoch is the same as the totalSupply for that epoch

eq(sharesAtEpoch, rewardsManager.totalSupply(epoch, address(this)), "Sum of user shares should equal total supply");

epoch++;

}

}

In the above since the RewardsManager contract checkpoints the totalSupply for each epoch and also tracks user shares for each epoch, the only additional tracking we need to add is an accumulator for the sum of user shares which we use to make our assertion against the totalSupply.

We can then start a new run of the fuzzer with our implemented property to see if it breaks. Ideally you should always run the fuzzer for around 5 minutes after implementing a property (or a few) because it allows you to quickly determine whether your property is correct or whether it breaks as a false positive (most false positives can be triggered with a relatively short run because they're either due to missing preconditions or a misunderstanding of how the system actually works in the property implementation).

Implementing many properties without running the fuzzer could result in many false positives that all need to be debugged separately and rerun to confirm they're resolved which ultimately slows down your implementation cycle.

Property refinement process

Very shortly after we start running the fuzzer it breaks the property, so we can stop the fuzzer and generate a reproducer using the Recon extension automatically (or use the Recon log scraper tool to generate one):

function test_property_totalSupplySolvency_0() public {

vm.warp(block.timestamp + 157880);

vm.roll(block.number + 1);

rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000,0x00000000000000000000000000000000DeaDBeef,1);

vm.warp(block.timestamp + 446939);

vm.roll(block.number + 1);

property_totalSupplySolvency();

}

We can see from this that the only state-changing call that was made in the sequence was to rewardsManager_notifyTransfer, which indicates that this is most likely a false positive, which we can confirm by checking the handler function implementation in AdminTargets:

abstract contract AdminTargets is

BaseTargetFunctions,

Properties

{

...

function rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(address from, address to, uint256 amount) public asAdmin {

rewardsManager.notifyTransfer(from, to, amount);

}

}

From the handler it becomes clear that the notifyTransfer function results in a call to the internal _handleDeposit function since the from address in the test is address(0):

function notifyTransfer(address from, address to, uint256 amount) external {

...

if (from == address(0)) {

/// @audit this line gets hit

_handleDeposit(msg.sender, to, amount);

} else if (to == address(0)) {

_handleWithdrawal(msg.sender, from, amount);

} else {

_handleTransfer(msg.sender, from, to, amount);

}

...

}

This results in deposited shares being accounted for the 0x00000000000000000000000000000000DeaDBeef address. Since we only sum over the share balance of all actors tracked in ActorManager in the property, it doesn't account for other addresses (such as 0x00000000000000000000000000000000DeaDBeef) having received shares, and so we get a 0 value for the sum in sharesAtEpoch and a value of 1 wei for the totalSupply at the current epoch.

To ensure we're only allowing transfers to actors tracked by our ActorManager we can clamp the to address to the currently set actor using _getActor():

function rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(address from, uint256 amount) public asAdmin {

rewardsManager.notifyTransfer(from, _getActor(), amount);

}

This type of clamping is often essential to prevent these types of false positives, so we don't implement them in a separate clamped handler (as this would still allow the fuzzer to call the unclamped handler with other addresses).

Clamping these values also doesn't overly restrict the search space because having random values passed in for users or tokens doesn't provide any benefit as they won't actually allow the fuzzer to reach additional states.

Any time there are addresses representing users or addresses representing tokens in handler function calls we can clamp using the

_getActor()and_getAsset()return values, respectively.

We can then run Echidna again to confirm whether this resolved our broken property as expected. After which we see that it still fails with the following reproducer:

function test_property_totalSupplySolvency_1() public {

rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000,1);

vm.warp(block.timestamp + 701427);

vm.roll(block.number + 1);

rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(0x00000000000000000000000000000000DeaDBeef,0);

vm.warp(block.timestamp + 512482);

vm.roll(block.number + 1);

property_totalSupplySolvency();

}

This should be an indicator to us that our initial understanding of how the system works was incorrect and we now need to look at the notifyDeposit implementation again more in depth to determine why the property still breaks.

We can see from the reproducer test that in the calls to rewardsManager_notifyTransfer, the first call calls the internal _handleDeposit function and the second call calls _handleTransfer:

function notifyTransfer(address from, address to, uint256 amount) external {

...

if (from == address(0)) {

/// @audit this is called first with 1 amount

_handleDeposit(msg.sender, to, amount);

} else if (to == address(0)) {

_handleWithdrawal(msg.sender, from, amount);

} else {

/// @audit this is called second with 0 amount

_handleTransfer(msg.sender, from, to, amount);

}

...

}

We can note that the first call is essentially registering a 1 wei deposit for the currently set actor (returned by _getActor()) and the second call is registering a transfer of 0 from the 0x00000000000000000000000000000000DeaDBeef address to the currently set actor.

Since the rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(0x00000000000000000000000000000000DeaDBeef,0) call is the last one, we know that something in the _handleTransfer call changes state in an unexpected way, which leads our property to break. Looking at the implementation of _handleTransfer, we see that since we're passing in a 0 value, the only state-changing calls it makes are to accrueUser:

function _handleTransfer(address vault, address from, address to, uint256 amount) internal {

uint256 cachedCurrentEpoch = currentEpoch();

// Accrue points for from, so they get rewards

accrueUser(cachedCurrentEpoch, vault, from);

// Accrue points for to, so they don't get too many rewards

accrueUser(cachedCurrentEpoch, vault, to);

/// @audit anything below these lines don't change state

unchecked {

// Add deposit data for to

shares[cachedCurrentEpoch][vault][to] += amount;

}

// Delete deposit data for from

shares[cachedCurrentEpoch][vault][from] -= amount;

}

This indicates to us that we are accruing shares for the user if time has passed since the last update:

function accrueUser(uint256 epochId, address vault, address user) public {

require(epochId <= currentEpoch(), "only ended epochs");

(uint256 currentBalance, bool shouldUpdate) = _getBalanceAtEpoch(epochId, vault, user);

if(shouldUpdate) {

shares[epochId][vault][user] = currentBalance;

}

...

}

Notably, however, there is no call to accrueVault in this transfer (unlike in the _handleDeposit and _handleWithdrawal functions), indicating that the user balances increase but the vault's totalSupply for the current epoch remains the same. We can then test whether this is the source of the issue by making a call to the accrueVault target handler:

function test_property_totalSupplySolvency_1() public {

rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000,1);

vm.warp(block.timestamp + 701427);

vm.roll(block.number + 1);

rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(0x00000000000000000000000000000000DeaDBeef,0);

rewardsManager_accrueVault(rewardsManager.currentEpoch(), address(this));

vm.warp(block.timestamp + 512482);

vm.roll(block.number + 1);

property_totalSupplySolvency();

}

which then allows the test to pass:

[PASS] test_property_totalSupplySolvency_1() (gas: 391567)

Suite result: ok. 1 passed; 0 failed; 0 skipped; finished in 7.33ms (2.83ms CPU time)

Looking at the accrueVault function, we see this is because it sets a new value for the totalSupply if the _getTotalSupplyAtEpoch function determines that it hasn't updated since the last epoch:

function accrueVault(uint256 epochId, address vault) public {

require(epochId <= currentEpoch(), "Cannot see the future");

(uint256 supply, bool shouldUpdate) = _getTotalSupplyAtEpoch(epochId, vault);

if(shouldUpdate) {

// Because we didn't return early, to make it cheaper for future lookbacks, let's store the lastKnownBalance

totalSupply[epochId][vault] = supply;

}

...

}

In our case, since there is no call to accrueVault in _handleTransfer but there is a call to accrueUser, the user is accounted shares for the epoch, but the vault isn't.

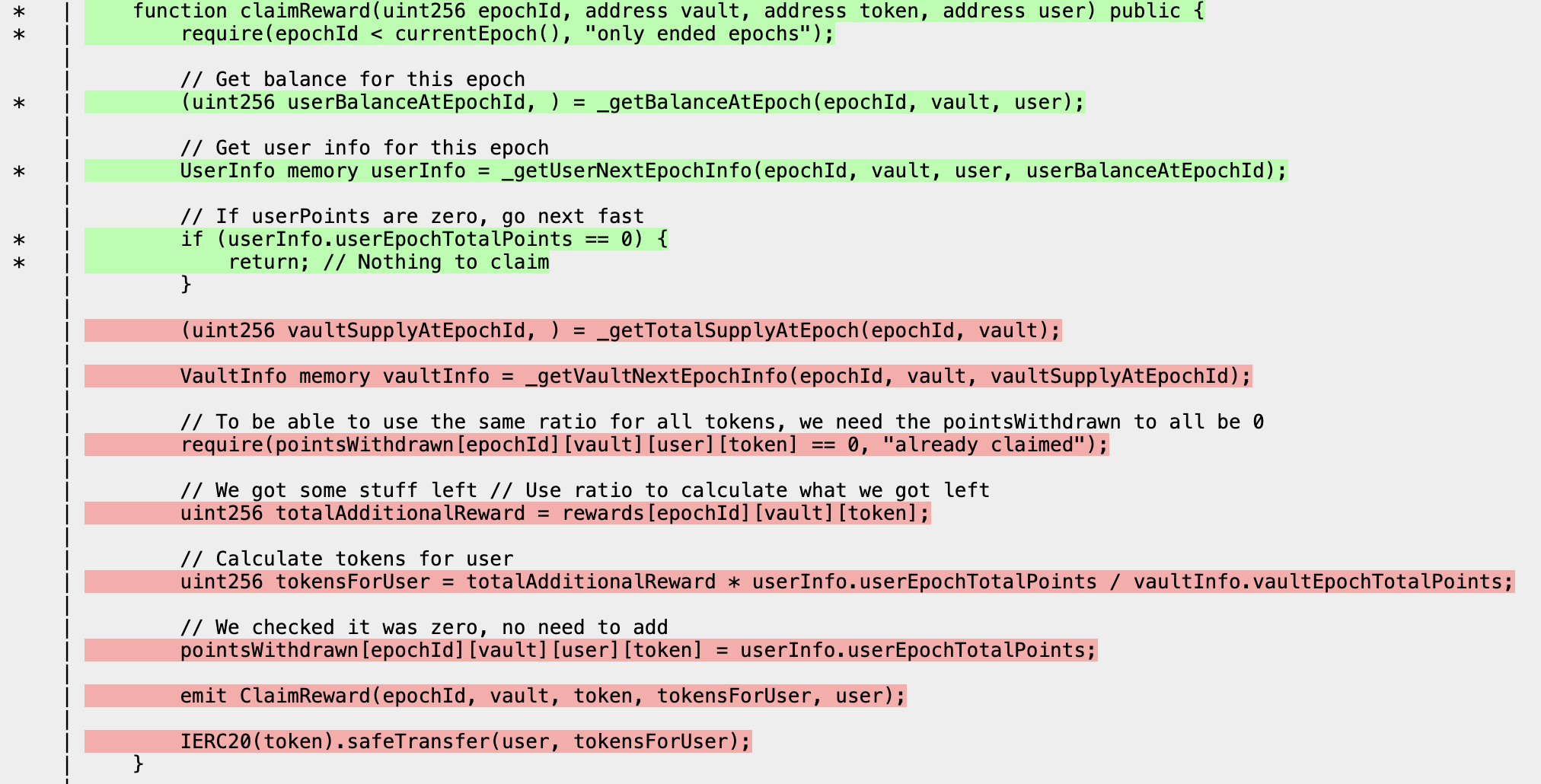

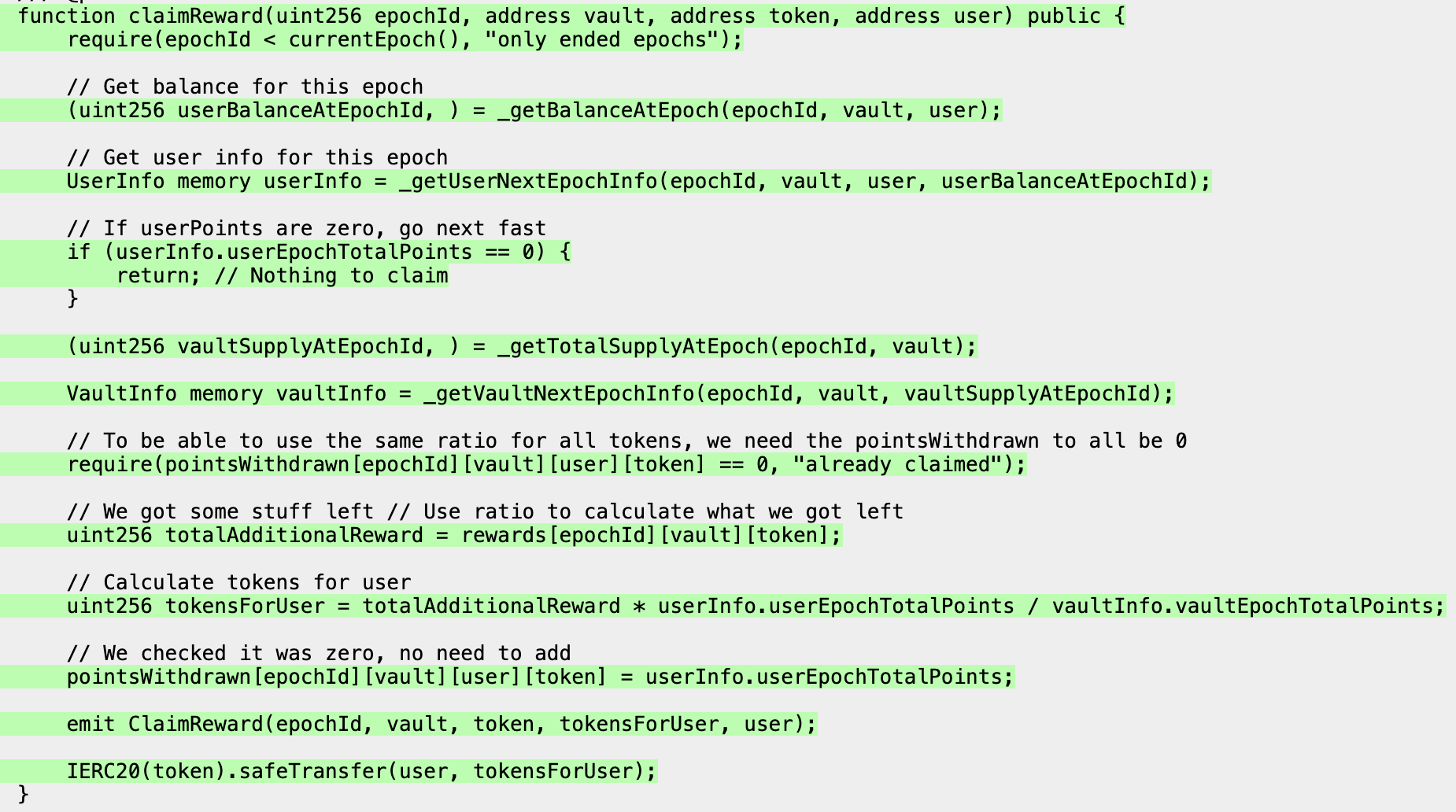

We can say that this is a real bug because it causes users to have claimable shares in an epoch in which there are no claimable shares tracked by the total supply. This would cause the following logic in the claimReward function to behave incorrectly due to a 0 return value from _getTotalSupplyAtEpoch, making a user unable to claim in an epoch for which they've accrued rewards:

function claimReward(uint256 epochId, address vault, address token, address user) public {

require(epochId < currentEpoch(), "only ended epochs");

// Get balance for this epoch

(uint256 userBalanceAtEpochId, ) = _getBalanceAtEpoch(epochId, vault, user);

// Get user info for this epoch

UserInfo memory userInfo = _getUserNextEpochInfo(epochId, vault, user, userBalanceAtEpochId);

// If userPoints are zero, go next fast

if (userInfo.userEpochTotalPoints == 0) {

return; // Nothing to claim

}

/// @audit this would return 0 incorrectly

(uint256 vaultSupplyAtEpochId, ) = _getTotalSupplyAtEpoch(epochId, vault);

VaultInfo memory vaultInfo = _getVaultNextEpochInfo(epochId, vault, vaultSupplyAtEpochId);

// To be able to use the same ratio for all tokens, we need the pointsWithdrawn to all be 0

require(pointsWithdrawn[epochId][vault][user][token] == 0, "already claimed");

// We got some stuff left // Use ratio to calculate what we got left

uint256 totalAdditionalReward = rewards[epochId][vault][token];

// Calculate tokens for user

// @audit this would use the wrong value

uint256 tokensForUser = totalAdditionalReward * userInfo.userEpochTotalPoints / vaultInfo.vaultEpochTotalPoints;

...

}

Now that we've identified the source of the issue, we can add the additional call to the accrueVault function in _handleTransfer:

function _handleTransfer(address vault, address from, address to, uint256 amount) internal {

uint256 cachedCurrentEpoch = currentEpoch();

// Accrue points for from, so they get rewards

accrueUser(cachedCurrentEpoch, vault, from);

// Accrue points for to, so they don't get too many rewards

accrueUser(cachedCurrentEpoch, vault, to);

// @audit added accrual to vault so tracking is correct

accrueVault(cachedCurrentEpoch, vault);

...

}

We can then run the fuzzer again to confirm that our property now passes. After doing so, however, we see that it once again fails with the following reproducer:

// forge test --match-test test_property_totalSupplySolvency -vvv

function test_property_totalSupplySolvency() public {

vm.warp(block.timestamp + 56523);

vm.roll(block.number + 1);

rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000,1);

switchActor(25183731206506529133541749133319);

vm.warp(block.timestamp + 947833);

vm.roll(block.number + 1);

rewardsManager_notifyTransfer(0x0000000000000000000000000000000000000000,0);

vm.warp(block.timestamp + 206328);

vm.roll(block.number + 1);

property_totalSupplySolvency();

}

which upon further investigation reveals that the call from notifyTransfer to _handleDeposit with a 0 value for amount causes the totalSupply to accrue for the vault but not the user since they have no value deposited:

function _handleDeposit(address vault, address to, uint256 amount) internal {

uint256 cachedCurrentEpoch = currentEpoch();

// @audit this accrues nothing since the actor that's switched to has no deposits

accrueUser(cachedCurrentEpoch, vault, to);

// @audit this accrues totalSupply with the amount deposited by the first actor

accrueVault(cachedCurrentEpoch, vault);

...

}

This should then cause us to reason that if we have a totalSupply greater than or equal to the shares accounted to users, then the system is solvent and able to repay all depositors, but if we have less than this amount, the system would be unable to repay all depositors. Which means that our property broke when it shouldn't have and so we can refactor it accordingly:

function property_totalSupplySolvency() public {

uint256 currentEpoch = rewardsManager.currentEpoch();

uint256 epoch;

while(epoch < currentEpoch) {

uint256 sharesAtEpoch;

// sum over all users

for (uint256 i = 0; i < _getActors().length; i++) {

uint256 shares = rewardsManager.shares(epoch, address(this), _getActors()[i]);

sharesAtEpoch += shares;

}

// check if solvency is met

lte(sharesAtEpoch, rewardsManager.totalSupply(epoch, address(this)), "Sum of user shares should equal total supply");

epoch++;

}

}

where our property now uses a less than or equal assertion (lte) instead of strict equality (eq), allowing the sum of user shares for an epoch to be less than the totalSupply for that epoch.

After running the fuzzer with this new property implementation for 5-10 minutes, it holds, confirming that it's now properly implemented.

The implementation property of the second property is left as an exercise to the reader, you can use the pseudocode to guide you and it should follow a similar implementation pattern as the first.

Conclusion

We've seen how invariant testing can often highlight misunderstandings of a system by giving you ways to easily test assumptions that are difficult to test with unit tests or stateless fuzzing. When these assumptions fail, it's either due to a false positive or a misunderstanding of how the system works, or both, as we saw above.

When you're forced to refactor your code to resolve an issue identified by a broken property, you can then run the fuzzer to confirm whether you resolved the issue for all cases. As we saw above this allowed us to see that our property implementation was overly strict and could be modified to be less strict.

One of the other key benefits of invariant testing besides explicitly identifying exploits is that it allows you to ask and answer questions about whether it's possible to get the system into a specific state. If the answer is yes and the state is unexpected, this can often be used as a precondition that can lead to an exploit of the system.

In part 4, we'll look at how a precondition was able to identify a multi-million dollar bug in a real-world codebase before it was pushed to production.

As always, if you have any questions reach out to the Recon team in the help channel of our discord.